ロドセン

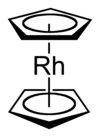

ロドセン(Rhodocene)、正式にはビス(η5-シクロペンタジエニル)ロジウム(II)は、[Rh(C5H5)2]の化学式を持つ化合物である。分子は、ロジウム原子がシクロペンタジエニル環として知られる5炭素からなる2つの平面に挟まれたサンドイッチ化合物の構造を持つ。ロジウム-炭素間に共有結合を持つ有機金属化合物である[2]。[Rh(C5H5)2]ラジカルは、150℃以上かまたは液体窒素(-196℃)で冷却トラップした際に見られる。室温では、1対のラジカルが結合して、二量体となる。二量体は黄色固体で、2つのシクロペンタジエニル環同士が結合している[1][3][4]。

| ロドセン | |

|---|---|

| |

ビス(η5-シクロペンタジエニル)ロジウム(II) | |

別称 ロドセン ジクロロペンタジエニルロジウム | |

| 識別情報 | |

| CAS登録番号 | 12318-21-7 |

| ChemSpider | 2339512 |

| |

| |

| 特性 | |

| 化学式 | C10H10Rh |

| モル質量 | 233.09 g mol−1 |

| 外観 | 黄色固体 (二量体)[1] |

| 融点 |

174℃で分解 (二量体)[1] |

| 水への溶解度 | ジクロロメタンに若干溶ける (二量体)[1] アセトニトリルに可溶[1] |

| 関連する物質 | |

| 関連物質 | フェロセン, コバルトセン, イリドセン, ビス(ベンゼン)クロム |

| 特記なき場合、データは常温 (25 °C)・常圧 (100 kPa) におけるものである。 | |

有機金属化学の歴史において、19世紀のツァイゼ塩の発見[5][6]とルードウィッヒ・モンドによるテトラカルボニルニッケルの発見[2]は、当時理解されていた化学結合モデルへの修正を迫った。ロドセンの鉄のアナログで初めてのメタロセンとなる[7]フェロセンが発見されると、このモデルはさらに修正を迫られた[8]。ロドセンの1価の陽イオンであるロドセニウムやそのコバルトやイリジウムのアナログ等のアナログ化合物と同様に[9]、フェロセンは化学的に異常に安定であることが発見された[10]。このような有機金属化学種の研究によって、これらの形成と安定性の両方を説明できる新しい結合モデルが発展した[11][12]。ロドセニウム/ロドセン系を含むサンドイッチ化合物の研究により、ジェフリー・ウィルキンソンとエルンスト・オットー・フィッシャーは、1973年のノーベル化学賞を受賞した[13]。

その安定性と合成の容易さのせいで、ロドセニウム塩は常に、不安定なロドセンや置換ロドセンの合成の出発物質となっている。当初の合成は、シクロペンタジエニルアニオンとトリス(アセトリアセトネート)ロジウム(III)を用いたものだが[9]、その後、気相酸化還元トランスメタル化[14]やハーフサンドイッチ化合物の前駆体を用いるもの[15]等、多数の合成法が報告されている。オクタフェニルロドセン(8つのフェニル基が置換した誘導体)は、大気中ですぐに崩壊したものの、室温で単離された初めてのロドセン置換体である。X線結晶構造解析によって、オクタフェニルロドセンは、ねじれ形配座を持つサンドイッチ構造であることが確認された[16]。1電子還元剤として有益なコバルトセンと異なり[17]、利用できるほどの安定性を持ったロドセンの誘導体は未だ発見されていない。

ロドセン化合物の医学用途への利用が研究され[18]、ロドセン誘導体を小さな癌の治療のための放射線調剤として用いる可能性が報告された[19][20]。ロドセン誘導体は、金属-金属相互作用を研究するための結合メタロセンの合成にも用いられる[21]。分子エレクトロニクスでの利用や触媒機構の研究への利用も提唱されている[22]。ロドセンの価値は、直接の利用というよりも、著名な化学系の結合や力学に関する洞察を与えてくれるところにある。

出典 編集

- ^ a b c d e El Murr, N.; Sheats, J. E.; Geiger, W. E.; Holloway, J. D. L. (1979). “Electrochemical Reduction Pathways of the Rhodocenium Ion. Dimerization and Reduction of Rhodocene”. Inorg. Chem. 18 (6): 1443-1446. doi:10.1021/ic50196a007.

- ^ a b Crabtree, R. H. (2009). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-470-25762-3. "

An industrial application of transition metal organometallic chemistry appeared as early as the 1880s, when Ludwig Mond showed that nickel can be purified by using CO to pick up nickel in the form of gaseous Ni(CO)4 that can easily be separated from solid impurities and later be thermally decomposed to give pure nickel.

... Recent work has shown the existence of a growing class of metalloenzymes having organometallic ligand environments - considered as the chemistry of metal ions having C-donor ligands such as CO or the methyl group

" - ^ Fischer, E. O.; Wawersik, H. (1966). “Uber Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen. LXXXVIII. Uber Monomeres und Dimeres Dicyclopentadienylrhodium und Dicyclopentadienyliridium und Uber Ein Neues Verfahren Zur Darstellung Ungeladener Metall-Aromaten-Komplexe” (German). J. Organomet. Chem. 5 (6): 559-567. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)85160-8.

- ^ Keller, H. J.; Wawersik, H. (1967). “Spektroskopische Untersuchungen an Komplexverbindungen. VI. EPR-spektren von (C5H5)2Rh und (C5H5)2Ir” (German). J. Organomet. Chem. 8 (1): 185-188. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)84718-X.

- ^ Hunt, L. B. (1984). “The First Organometallic Compounds: William Christopher Zeise and his Platinum Complexes”. Platinum Metals Rev. 28 (2): 76-83.

- ^ Zeise, W. C. (1831). “Von der Wirkung zwischen Platinchlorid und Alkohol, und von den dabei entstehenden neuen Substanzen” (German). Ann. der Physik 97 (4): 497-541. Bibcode: 1831AnP....97..497Z. doi:10.1002/andp.18310970402.

- ^ Federman Neto, A.; Pelegrino, A. C.; Darin, V. A. (2004). “Ferrocene: 50 Years of Transition Metal Organometallic Chemistry - From Organic and Inorganic to Supramolecular Chemistry”. ChemInform 35 (43). doi:10.1002/chin.200443242. (Abstract; original published in Trends Organomet. Chem., 4:147-169, 2002)

- ^ Laszlo, P.; Hoffmann, R. (2000). “Ferrocene: Ironclad History or Rashomon Tale?”. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39 (1): 123-124. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<123::AID-ANIE123>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10649350.

- ^ a b Cotton, F. A.; Whipple, R. O.; Wilkinson, G. (1953). “Bis-Cyclopentadienyl Compounds of Rhodium(III) and Iridium(III)”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 75 (14): 3586-3587. doi:10.1021/ja01110a504.

- ^ Kealy, T. J.; Pauson, P. L. (1951). “A New Type of Organo-Iron Compound”. Nature 168 (4285): 1039-1040. Bibcode: 1951Natur.168.1039K. doi:10.1038/1681039b0.

- ^ Mingos, D. M. P. (2001). “A Historical Perspective on Dewar's Landmark Contribution to Organometallic Chemistry”. J. Organomet. Chem. 635 (1-2): 1-8. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)01155-X.

- ^ Mehrotra, R. C.; Singh, A. (2007). Organometallic Chemistry: A Unified Approach (2nd ed.). New Delhi: New Age International. pp. 261-267. ISBN 978-81-224-1258-1

- ^ “The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1973”. Nobel Foundation. 2010年9月12日閲覧。

- ^ Jacobson, D. B.; Byrd, G. D.; Freiser, B. S. (1982). “Generation of Titanocene and Rhodocene Cations in the Gas Phase by a Novel Metal-Switching Reaction”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104 (8): 2320-2321. doi:10.1021/ja00372a041.

- ^ He, H. T. (1999). Synthesis and Characterisation of Metallocenes Containing Bulky Cyclopentadienyl Ligands (PhD thesis). University of Sydney. OCLC 222646266

- ^ Collins, J. E.; Castellani, M. P.; Rheingold, A. L.; Miller, E. J.; Geiger, W. E.; Rieger, A. L.; Rieger, P. H. (1995). “Synthesis, Characterization, and Molecular-Structure of Bis(tetraphenylcyclopentadienyl)rhodium(II)”. Organometallics 14 (3): 1232-1238. doi:10.1021/om00003a025.

- ^ Connelly, N. G.; Geiger, W. E. (1996). “Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry”. Chem. Rev. 96 (2): 877-910. doi:10.1021/cr940053x. PMID 11848774.

- ^ Pruchnik, F. P. (2005). “45Rh — Rhodium in Medicine”. In Gielen, M.; Tiekink, E. R. T. Metallotherapeutic Drugs and Metal-Based Diagnostic Agents: The Use of Metals in Medicine. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 379–398. doi:10.1002/0470864052.ch20. ISBN 0-470-86403-6

- ^ Wenzel, M.; Wu, Y. (1988). “Ferrocen-, Ruthenocen-bzw. Rhodocen-analoga von Haloperidol Synthese und Organverteilung nach Markierung mit 103Ru-bzw. 103mRh” (German). Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. A. 39 (12): 1237–1241. doi:10.1016/0883-2889(88)90106-2. PMID 2851003.

- ^ Wenzel, M.; Wu, Y. F. (1987). “Abtrennung von [103mRh]Rhodocen-Derivaten von den Analogen [103Ru]Ruthenocen-Derivaten und deren Organ-Verteilung” (German). Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. A. 38 (1): 67–69. doi:10.1016/0883-2889(87)90240-1. PMID 3030970.

- ^ Barlow, S.; O'Hare, D. (1997). “Metal–Metal Interactions in Linked Metallocenes”. Chem. Rev. 97 (3): 637–670. doi:10.1021/cr960083v.

- ^ Wagner, M. (2006). “A New Dimension in Multinuclear Metallocene Complexes”. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (36): 5916–5918. doi:10.1002/anie.200601787.