CXCL1

CXCL1(C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1)は、CXCケモカインファミリーに属する低分子量タンパク質である。いくつかの免疫系細胞(特に好中球[3][4])やその他の非造血系細胞を損傷部位や感染部位へ誘引する化学誘引物質として作用し、免疫応答や炎症応答の調節に重要な役割を果たす。以前はGRO1 oncogene、GROα、NAP-3(neutrophil-activating protein 3)、MGSA-α(melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha)といった名称で呼ばれていた。CXCL1は、BALB/c-3T3マウス胎児線維芽細胞に対するPDGF刺激によって誘導される遺伝子のcDNAライブラリから初めてクローニングされ、ニトロセルロースコロニーハイブリダイゼーションアッセイ時の位置から"KC"と命名された[5]。この記号は"keratinocytes-derived chemokine"の頭文字をとったものと誤解されていることがある。ラットのCXCL1は、NRK-52E細胞へのIL-1β、LPS刺激によって産生される、好中球を誘引するサイトカイン(cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant, CINC)の特性解析よって報告された[6]。ヒトでは、このタンパク質はCXCL1遺伝子にコードされており[7]、この遺伝子は他のCXCケモカインの遺伝子と共に4番染色体に位置している[8]。

構造と発現 編集

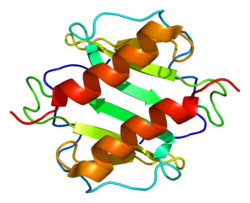

CXCL1は単量体と二量体の双方として存在し、どちらの形態でもケモカイン受容体CXCR2に結合することができる。しかしながら、CXCL1は高濃度(μM濃度)でのみ二量体化するのに対し、正常な条件下でのCXCL1の濃度はnMもしくはpMレベルである。このことは野生型CXCL1は単量体として存在している可能性が高く、二量体型のCXCL1は感染時または損傷時にのみ存在することを意味している。CXCL1の単量体は3本の逆平行βストランドとC末端のαヘリックスから構成され、このαヘリックスと最初のβストランドが二量体型構造の形成に関与している[9]。

正常な条件下ではCXCL1は恒常的には発現しておらず、マクロファージ、好中球などの免疫細胞や上皮細胞[10][11]、そしてTh17細胞によって産生される。その発現はIL-1やTNF-α、そしてTh17細胞自身によって産生されるIL-17によっても間接的に誘導される[12]。発現は主に炎症に関与するNF-κBまたはC/EBPβシグナル伝達経路の活性化によって主に開始され、その他の炎症性サイトカインの産生が引き起こされる[12]。

機能 編集

CXCL1はIL-8(CXCL8)と同様の役割を果たしている可能性がある。受容体であるCXCR2への結合後、CXCL1はPI3Kγ/Akt、ERK1/ERK2などのMAPキナーゼ、PLCβシグナル伝達経路を活性化する。CXCL1は炎症応答時に高レベルで発現し、炎症過程に寄与する[13]。CXCL1は創傷治癒や腫瘍形成過程にも関与している[14][15][16]。

がんにおける役割 編集

CXCL1は血管新生と動脈形成に関係しており[17]、腫瘍のプログレッションの過程で作用していることも示されている。乳がん、胃がん、大腸がん、肺がんなどさまざまな腫瘍の発生におけるCXCL1の役割がいくつかの研究で記載されている[18][19][20]。また、CXCL1はヒトメラノーマ細胞から分泌されて分裂促進因子としての作用を持ち、メラノーマの病因への関与が示唆されている[21][22][23]。

神経系と感作における役割 編集

CXCL1はオリゴデンドロサイト前駆細胞の遊走を阻害することで、脊髄の発生に関与している[24]。CXCL1の受容体であるCXCR2は脳と脊髄において神経細胞とオリゴデンドロサイトで発現しており、またアルツハイマー病、多発性硬化症、脳損傷などの中枢神経系の病理過程においてはミクログリアでも発現している。マウスにおける初期の研究では、CXCL1は多発性硬化症の重症度を低下させることが示されており、神経保護機能を持つ可能性がある[25]。一方、末梢においてはCXCL1はプロスタグランジンの放出に寄与して痛覚に対する感受性を高め、組織への好中球のリクルートを介して侵害受容感作を駆動する。ERK1/ERK2キナーゼのリン酸化とNMDA受容体の活性化は、c-FosやCOX-2など慢性疼痛を誘発する遺伝子の転写をもたらす[13]。

出典 編集

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000163739 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Neutrophil-activating properties of the melanoma growth-stimulatory activity”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 171 (5): 1797–1802. (May 1990). doi:10.1084/jem.171.5.1797. PMC 2187876. PMID 2185333.

- ^ “High- and low-affinity binding of GRO alpha and neutrophil-activating peptide 2 to interleukin 8 receptors on human neutrophils”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89 (21): 10542–10546. (November 1992). Bibcode: 1992PNAS...8910542S. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.21.10542. PMC 50375. PMID 1438244.

- ^ “Molecular cloning of gene sequences regulated by platelet-derived growth factor”. Cell 33 (3): 939–947. (July 1983). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90037-5. PMID 6872001.

- ^ “Purification and characterization of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant produced by epithelioid cell line of normal rat kidney (NRK-52E cell)”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 161 (3): 1093–1099. (June 1989). doi:10.1016/0006-291X(89)91355-7. PMID 2662972.

- ^ “Identification of three related human GRO genes encoding cytokine functions”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (19): 7732–7736. (October 1990). Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.7732H. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.19.7732. PMC 54822. PMID 2217207.

- ^ “Molecular characterization and chromosomal mapping of melanoma growth stimulatory activity, a growth factor structurally related to beta-thromboglobulin”. The EMBO Journal 7 (7): 2025–2033. (July 1988). doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03042.x. PMC 454478. PMID 2970963.

- ^ “Chemokine CXCL1 dimer is a potent agonist for the CXCR2 receptor”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 288 (17): 12244–12252. (April 2013). doi:10.1074/jbc.m112.443762. PMC 3636908. PMID 23479735.

- ^ “Cloning and sequencing of a new gro transcript from activated human monocytes: expression in leukocytes and wound tissue”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 10 (10): 5596–5599. (October 1990). doi:10.1128/mcb.10.10.5596. PMC 361282. PMID 2078213.

- ^ “Constitutive and stimulated MCP-1, GRO alpha, beta, and gamma expression in human airway epithelium and bronchoalveolar macrophages”. The American Journal of Physiology 266 (3 Pt 1): L278–L286. (March 1994). doi:10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.3.L278. PMID 8166297.

- ^ a b “Th17 cells regulate the production of CXCL1 in breast cancer”. International Immunopharmacology 56: 320–329. (March 2018). doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2018.01.026. PMID 29438938.

- ^ a b “CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in pathological pain: Role in peripheral and central sensitization”. Neurobiology of Disease 105: 109–116. (September 2017). doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2017.06.001. PMID 28587921.

- ^ “Delayed wound healing in CXCR2 knockout mice”. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 115 (2): 234–244. (August 2000). doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00034.x. PMC 2664868. PMID 10951241.

- ^ “The tumorigenic and angiogenic effects of MGSA/GRO proteins in melanoma”. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 67 (1): 53–62. (January 2000). doi:10.1002/jlb.67.1.53. PMC 2669312. PMID 10647998.[リンク切れ]

- ^ “Enhanced tumor-forming capacity for immortalized melanocytes expressing melanoma growth stimulatory activity/growth-regulated cytokine beta and gamma proteins”. International Journal of Cancer 73 (1): 94–103. (September 1997). doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<94::AID-IJC15>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 9334815.

- ^ “CXCL1 promotes arteriogenesis through enhanced monocyte recruitment into the peri-collateral space”. Angiogenesis 18 (2): 163–171. (April 2015). doi:10.1007/s10456-014-9454-1. PMID 25490937.

- ^ “Complementary action of CXCL1 and CXCL8 in pathogenesis of gastric carcinoma”. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 11 (2): 1036–1045. (2018-02-01). PMC 6958037. PMID 31938199.

- ^ “Interaction between Tumor-Associated Dendritic Cells and Colon Cancer Cells Contributes to Tumor Progression via CXCL1”. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19 (8): 2427. (August 2018). doi:10.3390/ijms19082427. PMC 6121631. PMID 30115896.

- ^ “Role of CXC group chemokines in lung cancer development and progression”. Journal of Thoracic Disease 9 (Suppl 3): S164–S171. (April 2017). doi:10.21037/jtd.2017.03.61. PMC 5392545. PMID 28446981.

- ^ “Constitutive overexpression of a growth-regulated gene in transformed Chinese hamster and human cells”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84 (20): 7188–7192. (October 1987). Bibcode: 1987PNAS...84.7188A. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.20.7188. PMC 299255. PMID 2890161.

- ^ “Melanoma growth stimulatory activity: isolation from human melanoma tumors and characterization of tissue distribution”. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 36 (2): 185–198. (February 1988). doi:10.1002/jcb.240360209. PMID 3356754.

- ^ “Role of CXCL1 in tumorigenesis of melanoma”. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 72 (1): 9–18. (July 2002). doi:10.1189/jlb.72.1.9. PMC 2668262. PMID 12101257.

- ^ “The chemokine receptor CXCR2 controls positioning of oligodendrocyte precursors in developing spinal cord by arresting their migration”. Cell 110 (3): 373–383. (August 2002). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00838-3. PMID 12176324.

- ^ “Neuroprotection and remyelination after autoimmune demyelination in mice that inducibly overexpress CXCL1”. The American Journal of Pathology 174 (1): 164–176. (January 2009). doi:10.2353/ajpath.2009.080350. PMC 2631329. PMID 19095949.

外部リンク 編集

- Human CXCL1 genome location and CXCL1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.