セルビアの聖ニコライ

この項目「セルビアの聖ニコライ」は翻訳依頼に出されており、翻訳者を求めています。 翻訳を行っていただける方は、翻訳前に翻訳依頼の「セルビアの聖ニコライ」の項目に記入してください。詳細は翻訳依頼や翻訳のガイドラインを参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2024年3月) |

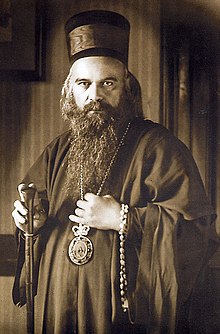

ニコライ・ヴェリミロヴィッチ(セルビア語キリル文字: Николај Велимировић; 1881年1月4日[O.S. 1880年12月23日] - 1956年3月18日[O.S. 1956年3月5日])は、セルビア正教会のオフリド大教会とジチャ大教会の司教(1920-1956年)。影響力のある神学的著述家であり、非常に優れた演説家でもある彼は、しばしば新しい金口イオアンと呼ばれ、歴史家のSlobodan G. Markovichは彼を「20世紀のセルビア正教会で最も影響力のある司教の一人」と呼んでいる。

| 聖人

ニコライ・ヴェリミロヴィッチ | |

|---|---|

| |

| 聖主教 | |

| Born | ニコライ・ヴェリミロヴィッチ 4 January 1881 Lelić, Serbia |

| Died | 18 March 1956 (aged 75) South Canaan, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 24 May 2003 by Serbian Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Lelić monastery, Serbia |

| Feast | 3 May (O.S. 20 May)[1][2] |

| Attributes | Vested as a bishop |

若い頃、赤痢で死にかけた彼は、生き延びたら自分の人生を神に捧げようと決心した。そして1909年、ニコライの名で修道士となった。聖職に叙階され、すぐにセルビア正教会の重要な指導者、代弁者となり、特に西側諸国との関係において重要な役割を果たした。第二次世界大戦でナチス・ドイツがユーゴスラビアを占領した際、ヴェリミロヴィッチは投獄され、最終的にはダッハウ強制収容所に連行された。

終戦時に連合国によって解放された後、彼はユーゴスラビア(戦後社会主義共和国となる)には戻らないことを選んだ。1946年にアメリカに移住し、1956年に亡くなるまでそこに留まった。彼はすべての東方正教会の一致を強く支持し、特に聖公会やエピスコパル教会と良好な関係を築いた。

2003年5月24日、セルビア正教会の聖会議により、オフリドとジチャの聖ニコライ(Свети Николај Охридски и Жички)として聖人に列せられたが、しばしばセルビアの聖ニコライ(Свети Николај Српски)と呼ばれる。

生涯 編集

早年 編集

ニコラ・ヴェリミロヴィッチとして、セルビア公国ヴァリェヴォの小さな村レリッチに生まれた。彼は、敬虔な農夫であったドラゴミルとカタリナ・ヴェリミロヴィッチ(旧姓フィリポヴィッチ)の間に生まれた9人の子どものうちの1番目であった。体が弱かったため、生まれてすぐにチェリエ修道院で洗礼を受けた。聖ニコラスが一家の守護聖人であったため、ニコラという名前が与えられた。神、イイスス・ハリストス、聖人の生涯、教会の祭日についての最初のレッスンは母親から受け、母親は定期的に祈りと聖体礼儀のためにチェリェ修道院に連れて行った[7]。

教育 編集

ヴェリミロヴィッチの正式な教育もまた、チェリエ修道院で始まり、ヴァリェヴォで継続された。陸軍士官学校への入学を志願したが、身体検査に合格しなかったため拒否された。ベオグラードの聖サヴァ神学校に入学し、標準的な科目とは別に、シェイクスピア、ヴォルテール、ニーチェ、マルクス、プーシキン、トルストイ、ドストエフスキーなど、東洋と西洋の作家の著作を数多く研究した。1905年に卒業した。

ニコラは聖サヴァ神学校の教授になることが決まっていたが、教師になる前に東方正教会の研究をさらに進める必要があると判断された。優秀な学生だった彼は、ロシアと西ヨーロッパで研究を続けることになった。彼には語学の才能があり、すぐにロシア語、フランス語、ドイツ語に精通するようになった。サンクトペテルブルクの神学アカデミーで学んだ後、スイスに渡り、ベルン大学の旧カトリック神学部で優秀な成績で神学博士号を取得した。

1908年、使徒教会の教義の基礎としてのキリストの復活への信仰と題する論文で神学博士号を取得。この原著はドイツ語で書かれ、1910年にスイスで出版され、後にセルビア語に翻訳された。哲学博士号取得のための学位論文はオックスフォードで準備され、ジュネーブでフランス語で発表された。タイトルは『バークレーの哲学』であった。

彼のイギリス滞在は、チャールズ・ディケンズ、バイロン卿、ジョン・ミルトン、チャールズ・ダーウィン、トーマス・カーライル、シェイクスピア、ジョージ・バークリーを引用または言及していることからもわかるように、彼の見解と教育に影響を残した。

修道生活 編集

In the autumn of 1909, Nikola returned home and became seriously ill with dysentery. He decided that if he recovered he would become a monk and devote his life to God. At the end of 1909 his health got better and he was tonsured a monk, receiving the name Nikolaj. He was soon ordained a hieromonk and then elevated to the rank of Archimandrite. In 1910 he was entrusted with a mission to Great Britain in order to gain the co-operation of the Church of England in educating the young students who had been evacuated when the Austrian, German and Bulgarian forces threatened to overwhelm the country.

Missions during World War I 編集

In his lifetime, Father Nikolaj visited the USA four times. He visited Britain in 1910. He studied English and was capable of addressing an audience and making a strong impression on the listeners. Shortly after the outbreak of World War I this contributed to his appointment by the Serbian government to a mission in the United States. In 1915, as an unknown Serbian monk, he toured most of the major U.S. cities, where he held numerous lectures, fighting for the union of the Serbs and South Slavic peoples. This mission gained ground: America sent over 20,000 volunteers to Europe, most of whom later fought on the Salonika front. During Velimirović's US-campaign occurred the great retreat of the Serbian Army through the mountains of Albania. He embarked home in 1916; as his country was now in enemy hands, he went to Britain instead. Not only did he fulfill his mission, but he was also awarded a Doctorate of Divinity honoris causa from the University of Cambridge.

He gave a series of notable lectures at St. Margaret's, Westminster, and preached in St. Paul's Cathedral, making him the first Eastern Orthodox Christian to preach at St Paul's.[3] Professor at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology Bogdan Lubardić has identified three phases in the development of Velimirovich's ideas: the pre-Ohrid phase (1902–1919), the Ohrid phase (1920–1936), and the post-Ohrid phase (1936–1956).[4]

Bishop 編集

In 1919, Archimandrite Nikolaj was consecrated Bishop of Žiča but did not remain long in that diocese, being asked to take over the office of Bishop in the Eparchy of Ohrid (1920-1931) and Eparchy of Ohrid and Bitola (1931-1936) in southern parts of Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1920, for the third time, he journeyed again to the United States, this time on a mission to organize the Serbian Orthodox Diocese of North America. He made another trip to the United States in 1927.

The 1930s 編集

German Chancellor Adolf Hitler awarded him with a civil medal in 1935 for his contribution in 1926 in renovation of the WWI German military cemetery in Bitola.[5] In 1936, he finally resumed his original office of Bishop in the Eparchy of Žiča, returning to the Monastery of Žiča not far distant from Valjevo and Lelić, where he was born. According to Jovan Byford, Velimirović's philosophy in 1939 got racist overtone typical of the time, as he considered the Serbs to be of "Aryan race".[6]

Detention and imprisonment in World War II 編集

During World War II, in 1941, as soon as the German forces occupied Yugoslavia, Bishop Nikolaj was arrested by the Nazis in the Monastery of Žiča, after which he was confined in the Monastery of Ljubostinja. Later he was transferred to the Monastery of Vojlovica (near Pančevo) in which he was confined together with the Serbian Patriarch Gavrilo V until the end of 1944. On 15 September 1944, both Patriarch Gavrilo V (Dožić) and Bishop Nikolaj were sent to Dachau concentration camp, which was at that time the main concentration camp for clerics arrested by the Nazis. Both Velimirović and Dožić were held as special prisoners (Ehrenhäftlinge) imprisoned in the so-called Ehrenbunker (or Prominentenbunker) separated from the work camp area, together with high-ranking Nazi enemy officers and other prominent prisoners whose arrests had been dictated by Hitler directly.

In August 1943 German general Hermann Neubacher became special emissary of the German Foreign Office for Southeastern Europe. From 11 September 1943, he was also made responsible for Albania. In December 1944 as part of a settlement of Neubacher with Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić Germans were release Velimirović and Dožić who were transferred from Dachau to Slovenia, as the Nazis attempted to make use of Patriarch Gavrilo's and Nikolaj's authority among the Serbs in order to gain allies in the anti-Communist movements.[7] Contrary to claims of torture and abuse at the camp, Patriarch Dožić testified himself that both he and Velimirović were treated normally. During his stay in Slovenia, Velimirović blessed volunteers of Dimitrije Ljotić and other collaborators and war criminals such as Dobroslav Jevđević and Momčilo Đujić.[8] In the final years of World War II in the book "Reči srpskom narodu kroz tamnički prozor" he says they the Jews condemned and killed Christ "suffocated by the stinking spirit of Satan", and further he writes that "Jews proved to be worse opponents of God than the pagan Pilate", "Devil teaches them so, their father", "the Devil taught them how to rebel against the Son of God, Jesus Christ."[9] Later, Velimirović and Patriarch Gavrilo (Dožić) were moved to Austria, and were finally liberated by the US 36th Infantry Division in Tyrol in 1945.[10]

Immigration and Last Years 編集

After the war he never returned to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, but after spending some time in Europe, he finally immigrated as a refugee to the United States in 1946. There, in spite of his health problems, he continued his missionary work, for which he is considered An Apostle and Missionary of the New Continent (quote by Fr. Alexander Schmemann), and has also been enlisted as an American Saint[要出典] and included on the icons and frescoes All American Saints.[11][12]

He taught at several Eastern Orthodox seminaries such as St. Sava's Seminary (Libertyville, Illinois), Saint Tikhon's Orthodox Theological Seminary and Monastery (South Canaan, Pennsylvania), and St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary (now in Crestwood, New York).

Literary criticism 編集

Amfilohije Radović points out that part of his success lies in his high education and ability to write well and his understanding of European culture.

Literary critic Milan Bogdanović claims that everything Velimirović wrote after his Ohrid years did nothing more than paraphrase Eastern Orthodox canon and dogma. Bogdanović views him as a conservative who glorified the Church and its ceremonies as an institution. Others say he brought little novelty into Eastern Orthodox thought. This, however, is explained by true Orthodox thought, because, as Saint John of Damascus writes, "It is for that reason that I say (teach) nothing of what is mine. I briefly express the thoughts and words passed down by Godly and wise men."[13]

Posthumous 編集

Velimirović died on 18 March 1956, while in prayer at the foot of his bed before the Liturgy, at St Tikhon's Orthodox Theological Seminary in South Canaan Township, Wayne County, Pennsylvania, where a shrine is established in his room. He was buried near the tomb of poet Jovan Dučić at the Monastery of St. Sava at Libertyville, Illinois. After the fall of communism, his remains were ultimately re-buried in his home town of Lelić on 12 May 1991, next to his parents and his nephew, Bishop Jovan Velimirović. On 19 May 2003, the Holy Assembly of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church recognized Bishop Nikolaj (Velimirović) of Ohrid and Žiča as a saint and decided to include him into the calendar of saints of Holy Orthodox Church (5 and 18 March).

Views 編集

Legacy 編集

A monastery is named after him in China, Michigan.

Porfirije, Serbian Patriarch stated that he is one of the three most notable Serb theologians to be recognized internationally.[14]

Velimirović is included in the book The 100 most prominent Serbs.[15]

Selected works 編集

- Моје успомене из Боке (1904) (My memories from Boka)

- Französisch-slavische Kämpfe in der Bocca di Cattaro (1910)

- Beyond Sin and Death (1914)

- Christianity and War: Letters of a Serbian to His English Friend (New York, 1915)

- The New Ideal in Education (1916)

- The Religious Spirit of the Slavs (1916)

- The Spiritual Rebirth of Europe (1917)

- Orations on the Universal Man (1920)

- Молитве на језеру (1922)

- Thoughts on Good and Evil (1923)

- Homilias, volumes I and II (1925)

- Читанка о Светоме краљу Јовану Владимиру ()

- The Prologue from Ohrid Archived 19 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. (1926)

- The Faith of Educated People (1928)

- The War and the Bible (1931)

- The Symbols and Signs (1932)

- The Chinese Martyrs by Saint Nikolai Velimirovich (Little Missionary, 1934 — 1938)

- "Immanuel" (1937)

- Теодул (1942)

- The Faith of the Saints (1949) (an Eastern Orthodox Catechism in English)

- The Life of Saint Sava (Zivot Sv. Save, 1951 original Serbian language version)

- Cassiana - the Science on Love (1952)

- The Only Love of Mankind (1958) (posthumously)

- The First Gods Law and the Pyramid of Paradise (1959) (posthumously)

- The Religion of Njegos (?)

- Speeches under the Mount (?)

- Emaniul (?) (Emmanuel)

- Vera svetih (?) (Faith of the holy)

- Indijska pisma (?) (Letters from India)

- Iznad istoka i zapada (?) (Above east and west)

- izabrana dela svetog Nikolaja Velimirovića (?) (Selected works of saint Nikolaj Velimirović)

References 編集

- ^ The Autonomous Orthodox Metropolia of Western Europe and the Americas (ROCOR). St. Hilarion Calendar of Saints for the year of our Lord 2004. St. Hilarion Press (Austin, TX). p.22.

- ^ "03 May 2017". Eternal Orthodox Church Calendar. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Markovich, Slobodan G. (2017). “Activities of Father Nikolai Velimirovich in Great Britain during the Great War”. Balcanica (XLVIII): 143–190. doi:10.2298/BALC1748143M. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_5544.

- ^ Markovich, Slobodan G. (2017). “Activities of Father Nikolai Velimirovich in Great Britain during the Great War”. Balcanica (48): 143–190. doi:10.2298/BALC1748143M. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_5544.

- ^ Byford 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Byford 2005, p. 30,171.

- ^ Byford 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Byford 2005, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Byford 2005, pp. 30–31.

- ^ “Saint Nikolaj (Velimirovic) - Canadian Orthodox History Project”. orthodoxcanada.ca. 2020年1月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Conciliar Press - All American Saints - 8 x 10 Icon”. 2011年7月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2009年6月30日閲覧。

- ^ “All Saints of North America | Flickr - Photo Sharing!”. Flickr (2009年4月27日). 2016年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Saint Nicodemos Publications”. Saintnicodemos.org. 2016年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ Beta (2021年3月6日). “Patrijarh Porfirije o episkopu Atanasiju: "I kada smo sa njim igrali fudbal i kada nas je vodio na Svetu Goru bio je tamo gde i sveti oci"” (英語). Nedeljnik. 2021年3月8日閲覧。

- ^ (セルビア語) 100 najznamenitijih Srba. Princip. (1993). ISBN 978-86-82273-01-1

Sources 編集

- Vuković, Sava (1998). History of the Serbian Orthodox Church in America and Canada 1891–1941. Kragujevac: Kalenić

- Byford, J.T. (2004). Canonisation of Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović and the legitimisation of religious anti-Semitism in contemporary Serbian society. East European Perspectives, 6 (3)

- Byford, J.T. (2004). From ‘Traitor’ to ‘Saint’ in Public Memory: The Case of Serbian Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović. Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism series (ACTA), No.22.

- Byford, J.T. "Canonizing the 'Prophet' of antisemitism: the apotheosis of bishop Nikolaj Velimirović and the legitimation of religious anti-semitism in contemporary Serbian society", RFE/RL Report, 18 February 2004, Volume 6, Number 4

- Byford, Jovan (2005). Potiskivanje i poricanje antisemitizma : sećanje na vladiku Nikolaja Velimirovića u savremenoj srpskoj pravoslavnoj kulturi. Belgrade: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji. ISBN 978-8-67208-117-6

- Byford, Jovan (2008). Denial and Repression of Antisemitism: Post-communist Remembrance of the Serbian Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-63977-615-9

- Byford, Jovan (2011). “Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović: "lackey of the Germans" or a "Victim of Fascism"?”. In Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola. Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 128–152. ISBN 978-0-230-27830-1

- Cohen, Philip J. (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-760-7

External links 編集

- Works by Nikolaj Velimirović at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Nikolaj Velimirović at Internet Archive