毛細管現象

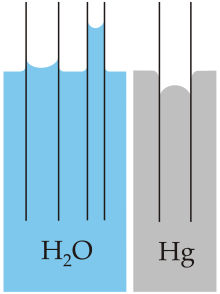

毛細管現象(もうさいかんげんしょう、英: capillary action)とは、細い管状物体(毛細管)の内側の液体が、外部からエネルギーを与えられることなく管の中を移動する物理現象である。毛管現象とも呼ばれる。地球上での重力に逆らえるほど上昇(場合によっては下降)することもある。主に静電気力が影響している。

| 連続体力学 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

例えば、ガラス容器に入った液体を側面から観察すると、容器の壁面と接している部分と離れた部分では液面の高さが異なっている。

表面張力・壁面のぬれやすさ・液体の密度によって液体上昇の高さが決まる。

表面張力を測定する方法の一つとなっている[1]。

原理 編集

厳密性を無視した簡単な原理を次に示す。

- 表面張力によって液面は縮まろうとする方向に力が加わっている。

- 壁面付近の傾きをもった液面が縮まろうとすることによって結果的に水面を持ち上げる。つまり、液体の上昇する力は壁面付近の表面張力の垂直成分に等しい。

- 上の二つの力と持ち上げた液体の重さがつりあうまで液面は上昇する。液体の重さは密度×体積(管断面積×高さ)で求まるが、細い管の場合はこの管断面積が微小となる。このため液面の上昇する高さは非常に大きいものとなる。

計算式 編集

液面の上昇高さh は、以下の式で与えられる。

- T = 表面張力

- θ = 接触角

- ρ = 液体の密度

- g = 重力加速度

- r = 管の内径(半径)

たとえば、海水面高度でガラス管と水の組み合わせの場合、

- T = 0.0728 N/m (20℃)

- θ = 20°

- ρ = 1000 kg/m3

- g = 9.80665 m/s²

となり、次の式で液面の上昇高さを計算できる。

ガラス管の半径がr = 0.05 mmであれば、液面の上昇は約28 cmとなる。

研究史 編集

毛細管現象について最初に記録を残したのは、15世紀末(1490年[1])のレオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチである[2][3]。その後、ガリレオの弟子のニッコロ・アギウンティ(Niccolò Aggiunti:1600–1635)も研究を行ったと言われている[4]。ボイルの法則で知られる、ロバート・ボイルは1660年に「フランスの好奇心の強い人物が細い管を水中に立てる管中の水面がいくらか上昇するのを観察した」と述べ、その後ワインで試したことや、全体に圧を下げても変わらなかったことを報告した[5]。

ボイルの研究を受けて、フランスのオノレ・ファブリ(Honoré Fabri)[6]やスイスのヤコブ・ベルヌーイ[7]らが研究を行い、細管の中では空気が液体より動きにくいので圧力差が生じる、というような説も出された。オランダのフォシウス[8](Isaac Vossius:1618–1689)、イタリアのジョヴァンニ・ボレリ[9]、フランスのルイ・カレ[10](Louis Carré:1663-1711)、イギリスのホークスビー[11](Francis Hauksbee:1660–1713、ニュートンの助手)やドイツのヴァイトブレヒト[12](Josias Weitbrecht:1702-1747)らは液体の粒子が互いに引き合い、壁に引かれるのだと考えた。

18世紀に入り、イギリスのトマス・ヤングとピエール=シモン・ラプラスがヤング・ラプラスの式を導き、ドイツの数学者、カール・フリードリヒ・ガウスも毛細管現象について研究した。イギリスのウィリアム・トムソン(ケルビン卿)は、気液海面の蒸気圧に関するケルビン方程式を導いた。フランツ・エルンスト・ノイマンは3つの相の接触点における平衡の解析した。

ちなみに1901年にアインシュタインが最初に発表した論文は毛細管現象に関するものであった。

参考文献 編集

- ^ a b 五十嵐保; 杉山均『流体工学と伝熱工学のための次元解析活用法』共立出版、2013年、36頁。ISBN 978-4-320-07189-6。

- ^ See:

- Manuscripts of Léonardo de Vinci (Paris), vol. N, folios 11, 67, and 74.

- Guillaume Libri, Histoire des sciences mathématiques en Italie, depuis la Renaissance des lettres jusqu'a la fin du dix-septième siecle [History of the mathematical sciences in Italy, from the Renaissance until the end of the seventeenth century] (Paris, France: Jules Renouard et cie., 1840), vol. 3, page 54. From page 54: "Enfin, deux observations capitales, celle de l'action capillaire (7) et celle de la diffraction (8), dont jusqu'à présent on avait méconnu le véritable auteur, sont dues également à ce brillant génie." (Finally, two major observations, that of capillary action (7) and that of diffraction (8), the true author of which until now had not been recognized, are also due to this brilliant genius.)

- C. Wolf (1857) "Vom Einfluss der Temperatur auf die Erscheinungen in Haarröhrchen" (On the influence of temperature on phenomena in capillary tubes) Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 101 (177) : 550–576 ; see footnote on page 551 by editor Johann C. Poggendorff. From page 551: " ... nach Libri (Hist. des sciences math. en Italie, T. III, p. 54) in den zu Paris aufbewahrten Handschriften des grossen Künstlers Leonardo da Vinci (gestorben 1519) schon Beobachtungen dieser Art vorfinden; ... " ( ... according to Libri (History of the mathematical sciences in Italy, vol. 3, p. 54) observations of this kind [i.e., of capillary action] are already to be found in the manuscripts of the great artist Leonardo da Vinci (died 1519), which are preserved in Paris; ... )

- ^ More detailed histories of research on capillary action can be found in:

- David Brewster, ed., Edinburgh Encyclopaedia (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Joseph and Edward Parker, 1832), volume 10, pp. 805–823.

- Maxwell, James Clerk; Strutt, John William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (英語). Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–275.

- John Uri Lloyd (1902) "References to capillarity to the end of the year 1900," Bulletin of the Lloyd Library and Museum of Botany, Pharmacy and Materia Medica, 1 (4) : 99–204.

- ^ In his book of 1759, Giovani Batista Clemente Nelli (1725–1793) stated (p. 87) that he had "un libro di problem vari geometrici ec. e di speculazioni, ed esperienze fisiche ec." (a book of various geometric problems and of speculation and physical experiments, etc.) by Aggiunti. On pages 91–92, he quotes from this book: Aggiunti attributed capillary action to "moto occulto" (hidden/secret motion). He proposed that mosquitoes, butterflies, and bees feed via capillary action, and that sap ascends in plants via capillary action. See: Giovambatista Clemente Nelli, Saggio di Storia Letteraria Fiorentina del Secolo XVII ... [Essay on Florence's literary history in the 17th century, ... ] (Lucca, (Italy): Vincenzo Giuntini, 1759), pp. 91–92.

- ^ Robert Boyle, New Experiments Physico-Mechanical touching the Spring of the Air, ... (Oxford, England: H. Hall, 1660), pp. 265–270. Available on-line at: Echo (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; Berlin, Germany).

- ^ See:

- Honorato Fabri, Dialogi physici ... ((Lyon (Lugdunum), France: 1665), pages 157 ff "Dialogus Quartus. In quo, de libratis suspensisque liquoribus & Mercurio disputatur. (Dialogue four. In which the balance and suspension of liquids and mercury is discussed).

- Honorato Fabri, Dialogi physici ... ((Lyon (Lugdunum), France: Antoine Molin, 1669), pages 267 ff "Alithophilus, Dialogus quartus, in quo nonnulla discutiuntur à D. Montanario opposita circa elevationem Humoris in canaliculis, etc." (Alithophilus, Fourth dialogue, in which Dr. Montanari's opposition regarding the elevation of liquids in capillaries is utterly refuted).

- ^ Jacob Bernoulli, Dissertatio de Gravitate Ætheris (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Hendrik Wetsten, 1683).

- ^ Isaac Vossius, De Nili et Aliorum Fluminum Origine [On the sources of the Nile and other rivers] (Hague (Hagæ Comitis), Netherlands: Adrian Vlacq, 1666), pages 3–7 (chapter 2).

- ^ Borelli, Giovanni Alfonso De motionibus naturalibus a gravitate pendentibus (Lyon, France: 1670), page 385, Cap. 8 Prop. CLXXXV (Chapter 8, Proposition 185.). Available on-line at: Echo (Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; Berlin, Germany).

- ^ Carré (1705) "Experiences sur les tuyaux Capillaires" (Experiments on capillary tubes), Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, pp. 241–254.

- ^ See:

- Francis Hauksbee (1708) "Several Experiments Touching the Seeming Spontaneous Ascent of Water," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 26 : 258–266.

- Francis Hauksbee, Physico-mechanical Experiments on Various Subjects ... (London, England: (Self-published), 1709), pages 139–169.

- Francis Hauksbee (1711) "An account of an experiment touching the direction of a drop of oil of oranges, between two glass planes, towards any side of them that is nearest press'd together," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 27 : 374–375.

- Francis Hauksbee (1712) "An account of an experiment touching the ascent of water between two glass planes, in an hyperbolick figure," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 27 : 539–540.

- ^ See:

- Josia Weitbrecht (1736) "Tentamen theoriae qua ascensus aquae in tubis capillaribus explicatur" (Theoretical essay in which the ascent of water in capillary tubes is explained), Commentarii academiae scientiarum imperialis Petropolitanae (Memoirs of the imperial academy of sciences in St. Petersburg), 8 : 261–309.

- Josia Weitbrecht (1737) "Explicatio difficilium experimentorum circa ascensum aquae in tubis capillaribus" (Explanation of difficult experiments concerning the ascent of water in capillary tubes), Commentarii academiae scientiarum imperialis Petropolitanae (Memoirs of the imperial academy of sciences in St. Petersburg), 9 : 275–309.